|

| Via Wikimedia Commons |

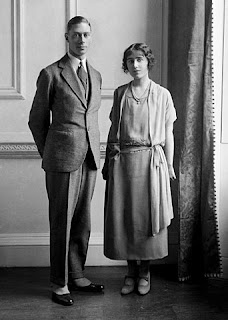

Beside her, Prince Albert is uncharacteristically serene. The second son of an overbearing father and a distant mother (who also happened to be King George VI and Queen Mary) and the product of neglectful, even abusive nursery staff, Albert Duke of York, was slender and sickly. Leg braces had forced most of the knock out of his knees but it would take years of speech therapy, encouraged and supported by Elizabeth, to control the anxious stammer he developed from his insecure upbringing. Compared to his confident, exuberant, athletic older brother the Prince of Wales, Bertie looked fairly pitiful. But, he was a hard worker, brave and tenacious. Despite lifelong battles with stomach ailments, which often sent him for long convalescences during the Great War, he had fought courageously on HMS Collingwood during the Battle of Jutland. After the war, he devoted himself to improving working conditions and even launched his own series of programs and camps for young man.

|

| From the Royal Collection via Wikimedia Commons |

Elizabeth thought that interest in her as a royal bride would soon fade. Once Bertie's older brother married and had children, Bertie would move further and further from the throne, and they would be able to simply enjoy their life together: dancing until the early hours in London or Paris, dashing off to country house parties, fishing in freezing Scottish rivers, interrupted occasionally by royal duties. She was grateful for this holiday far from the attention back in Britain. What an adventure! But, even their African safari honeymoon had been interrupted by their royal responsibilities.

Embed from Getty Images

Now, however, they were just two young people tramping across the African landscape. Their trip had been planned to serve the British Empire, which was still strong and growing in the 1920s. In fact, Britain had taken over two million square miles from Germany after the Great War, but the strains on the continent were still growing, too. The government sent the happy, young couple to shake hands and say thank you to the African nations who had sacrificed to much in the war. They were the first British royals to visit East Africa in nearly 15 years, and so they traveled far and wide and people traveled from either further afield to see them. They came to Kenya, Uganda and the Sudan from the Congo and Nyasaland. The couple opened parks and clubs, met with government and tribal officials, attended Christmas Day services at an English church and again at an African one. Engagement after engagement, they smiled and charmed their way across African society at every level.

Until, at last, they were granted this treat: three weeks on a safari, a kind of belated honeymoon for the Duke and Duchess, who had married 20 months earlier. The couple who had spent their courtship and early marriage in the clubs all night and sleeping until the crack of noon, soon found themselves enjoying early mornings creeping through bushes to watch zebras, rhinos, lions and giraffes. They walked and walked, as much as 20 miles in a day, soaking in the tropical sun and enjoying their wild new companions. Elizabeth was a keen reporter in her letters back home, "Rhinos are very funny," she wrote, "very fussy, like old gentlemen, & very busy all the time, quite ridiculous in fact."

They camped in wild areas on some nights, unable to sleep for the noise of lions and hyenas circling round, unaware of the royal status of the humans in the tents. They shot big game. The Duchess herself took to rifle, becoming quite a crack at killing zebras and rhinos, but frequently opining that it broke her heart to do so. When at last they drove 200 miles back to civilization in Nairobi, Elizabeth had her hair washed and set for the first time in weeks. "Feel clean again!" she told her diary.

The official royal duties carried on as though they had never ceased. More clubs, more dinners, more railway platforms, more tribal ceremonies before being interrupted by another little safari, walking and boating in Uganda, where she had a close encounter with an elephant. "It came bearing down on us at full speed, so we slipped behind an ant hill & flew past."

Through all the adventure, one thing was clear to the couple's hosts and guides: the Yorks were in love. "Left no doubt as to whether it was a love match," one of their guides wrote. "He utterly adores her."

The official tour continued down the Nile into Sudan, still rife with anti-British rebellions. Then, it was on to Tonga. At every stop, they were greeted by British officials and tribal leaders and welcomed with great ceremony to see new buildings and inspect new dams. After nearly four months of interwoven royal tour and private safari, the Duke and Duchess at last set sail back to Britain. "It is very sad having nothing to get up for now!" she confided to her diary.

Throughout her long life, Elizabeth would return again and again to the African continent. Perhaps the most famous visit would be the couple's post-World War II tour of South Africa and Rhodesia. By then, her brother-in-law had shirked the throne, making the Duke and Duchess King and Queen. They triumphantly led the nation and the soon-to-crumble empire through the war and emerged on the other side ready to celebrate a new future. For this tour, they brought along their daughters, Margaret and Elizabeth, who on that trip turned 21 and pledged that her whole life, "whether it be long or short shall be devoted...to the great imperial family to which we all belong."

SOUTH AFRICA 1947

Embed from Getty Images

Throughout the years of her long widowhood, Elizabeth, now best known as The Queen Mother, her gentle smile and untiring devotion to duty helped heal many of the rifts that decolonization brought as the Empire transitioned to the Commonwealth. In 1953, she made her first tour as a widow back to Rhodesia. For the first time, Bertie was not by her side as she retraced many of the steps that they had taken as a family in 1947. On a visit to Kenya in 1959 with Margaret, she arrived following a terrible drought. In her opening speech, she hoped for rain. Within an hour, the rains finally arrived and she was hailed as a rain-maker by the local Masai. A year later, she was back in Rhodesia to open a dam, where she understood the need to shift to black rule, but was concerned about the growing gulf between whites and blacks. When the divide erupted into a white-ruled Rhodesia and an apartheid South Africa, she was deeply disappointed but never surrendered her interest in these countries. When apartheid ended and South Africa was readmitted to the Commonwealth, she was beaming with delight at the celebration service in London.

Embed from Getty Images

Elizabeth continued her world travels well into her 90s, rarely slowing her pace for the younger people who traveled with her. Often, they would schedule "time off" during her tours, but she always filled those hours up with some new adventure, just as she had done so many decades earlier following the Nile with her husband.

In her last moments, 50 years and one month after Bertie's death and nearly 80 years after that first safari dawn, Elizabeth's thoughts might have slipped back to those precious, private moments when it was just her and her sweetheart alone in a giant world far from the crown they would carry.

For More About Elizabeth

No comments:

Post a Comment